MECHANISATION OF AGRICULTURE IN SUB-SAHARAN AFRICA

By Trevor Bullen, BSc Agricultural Engineering, Contributing Author.

World Bank indicators show that Sub- Saharan Africa has 1 billion hectares of agricultural land which is approximately 42% of the land in sub-Saharan Africa. Of this, approximately 25% is currently under crop today, the majority of which is on a seasonal basis. The population in the region is some 856 million, a population density of approximately 40 per square kilometer compared to 116 in Europe.

The numbers above could suggest that there is an abundance of agricultural land in Africa for expansion of agricultural operations. The fact is that there is a predominance of rural dwellers who rely on land for subsistence farming, most of which is under-utilised. At the same time, it is well documented that many of the rural population of sub-Saharan Africa are undernourished, if not malnourished, this is a result of an unbalanced diet as much as a shortage of food at certain times of the year.

The problem to be addressed immediately is therefore how to increase the quality and quantity of food supplies to the existing population. This is an issue being addressed by many NGOs and Development Agencies, with varying degrees of success. It normally focuses on the supply of inputs in order to increase the productivity per hectare and also by encouraging issues related to the Value Chain of processing of basic commodities into a higher value, more readily saleable, product. All these initiatives are laudable but are having limited impact – the data of the number of people on the poverty line speaks for itself.

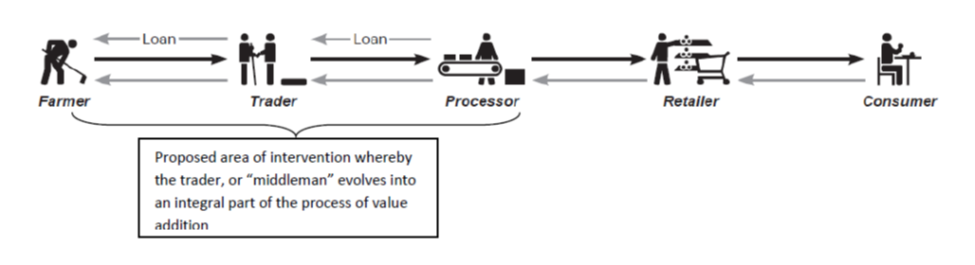

Figure 1 – The Value Chain and actors in an integrated agro-industrial operation

Of greater concern in terms of scale is the fact, which is well documented, that the population of the World will increase by 2 billion souls, to 9 billion, by 2050. It is also well documented that the majority of the increase will be within sub-Saharan Africa. The net situation is that a solution to increase productivity must be found to solve a problem that will impact 2.7 billion people directly in the region, in a period of 30 years, when previous efforts to solve the same issues over the past 30 years have not provided a solution.

The primary question therefore is how to increase production of commodities and secondly how to process those commodities to ensure that the quality meets import substitution standards. The reason for this second issue is that in many African countries there is a fast growing middle class with a sophisticated expectation of processed products and product quality along with the disposable income to purchase. They have come to expect a standard and successive Government have chosen to spend foreign exchange on importing processed commodities rather than facilitate national capabilities to the detriment of local production facilities.

At the same time we have the abject poverty and nutritional deficit of the rural population. Issues facing the rural producer communities are:

- Land Tenure – in many cases the operator on a parcel of land does not have ownership despite, in many cases, generations of occupation. Land is sometimes owned by absentee landlords who charge a rent or tithe to the farmer, further increasing the burden on the rural producer community.

- Parcel size – due to factors of inheritance and land ownership, plot size is diminishing providing a stress on families to produce sufficient subsistence product. This problem is exacerbated by a lack of young men to work the land as a result of urban drift.

- Availability of Funds – agricultural production is capital intensive in that all products required to develop a crop, i.e. seed, fertiliser, chemicals and other inputs are required prior to season start and no return is obtained for the growing and harvesting season of a minimum of 120 days. Also many in the producer community retain a percentage of their crop as a “bank”.

- Access to funds – the majority of farmers have no access to traditional banking, Micro-Financing institutions are more focused on trade finance, i.e. a quick return. The 3 to 4 month agricultural cycle puts an interest burden on the farmer that is not sustainable.

- Access to quality inputs – in too many cases the necessary inputs are adulterated by unscrupulous dealers in a quest to increase revenue for themselves to the detriment of the producer community.

- Extension Services – In many cases the mechanism for farmers to obtain advice on modalities to increase efficiency and consequently increase yield per ha., is not available due to a lack of services provided by Government.

All the foregoing are issues that are being addressed, in some way, shape or form by various agencies and Governments, and need to be resolved if the producer community are to be able to reach the goal of a sustainable, and profitable, operation. Many efforts need a radical review if the current challenges are to be overcome and those posed within the next 30 years are to be resolved before a catastrophe occurs.

An issue that has an increasing popularity is Mechanisation. This is mentioned as a modality to resolve the lack of labour in rural areas, as a result of urban drift. It is also mentioned a “cure all” for speed of operation and a method to increase yield. In many cases it is referred to as “Tractorisation”, even FAO describes it in this way.

Mechanisation is a process that should take the drudgery out of agriculture at every stage of the agricultural process, i.e. Land preparation, planting, harvesting, primary processing, secondary processing, manufacturing and sale of finished products. All these are part of the Value Chain, as shown above in Figure 1, where the process is integrated and where the farmer can benefit from the processes with the pertinent interventions.

The perspective of many in the development sector is that the supply of a tractor, hence the term tractorisation, is the solution for increased productivity through mechanisation. The fact of the matter is that the tractor, in and of itself, will produce nothing more than a financial burden on the farmer if the operation carried out by the tractor operator does not result in more efficient operations and an increase of yield.

There is a history of Governments in the region over many years, from the 1980’s, of establishing Tractor Hiring Units, these have a record unblemished by success. The reason for failure is that the end user, the farmer, had no vested interest in, or control over, the operation. In addition, neither the farmer, nor the tractor operator, had sufficient knowledge with regard to the outcome of the specific activity, i.e. land preparation is done to create a suitable tilt as a seed bed to ensure optimum conditions for seed germination and growth.

Too often, even today, the operations carried out by the tractor operator are to achieve some sort of field coverage as quickly as possible because he is paid on a hectare covered basis. The operation is often with an initial pass of a disc plough (a primary, not secondary, cultivation tool) that is often set up incorrectly, as seen in Figure 2, and then covering the poor quality work done by a quick pass with a disc harrow, deluding the farmer that he has a seedbed. In fact what he has is a hard pan a few inches down, with pulverized soil on the surface that will wash away with the first rain, often carrying seed with it.

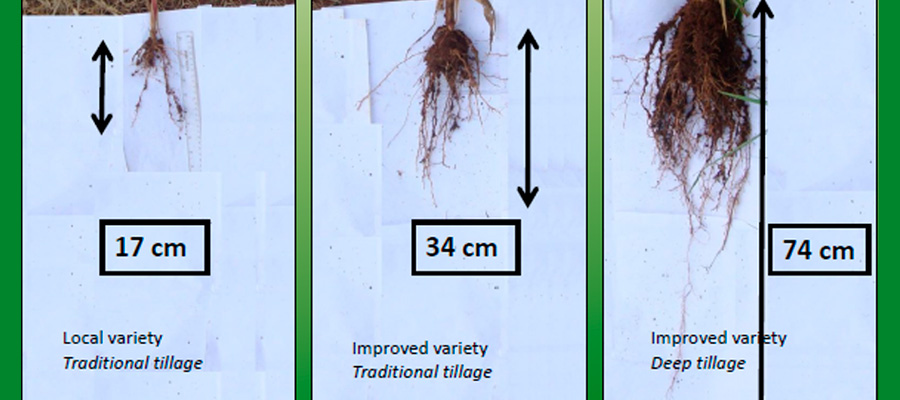

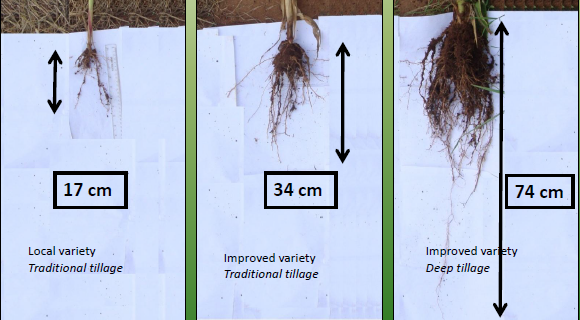

In terms of seedbed preparation, the tractor must create the ideal environment for the seed in all stages of the agronomic process. This means that the seed can germinate and get access to nutrients and water and that the soil will retain moisture and stop runoff. The picture below demonstrates the benefits of quality land preparation on the root development of a maize crop with good tillage making a difference. Provision of high quality certified seed will not be the “silver bullet” on yield increase.

Figure 3 – A demonstration of how good cultivation impacts on root development, Good Roots equals Good Crops!

Therefore the focus of machinery and equipment sellers needs to be on the implements that are powered by a tractor, not on the tractor itself. These implements include soil engaging tools, harvesting tools and primary processing tools to improve the quality of the commodity produced, taking the drudgery out of the operations that will allow and ensure optimum yields and optimum prices obtained by the buyers of the commodity.

Once the farmer sees an increase in revenue from the processes powered by the tractor, there will be an increase in demand for mechanisation services as well as the implements that actually provide the function that results in increased revenues. The net result is an increase in the requirement for tractors to power the various operations. Suppliers of tractors need to provide a holistic service in terms of maintenance and repair of the units to ensure optimum output. In the absence of Extension Services personnel with an understanding of the capabilities of implements, the tractor retailer would also need to provide advice on the capabilities of his units.

Conclusion

Tractors, in and of themselves, are of little use to the Producer community and consequently to the Consumer community. To make the use of tractors sustainable, profitable and to develop the market to the benefit of all players, utilisation needs to be optimised be it on large or small scale farms. This includes appropriate methods of irrigation to allow and facilitate better utilisation of land. Land is a finite resource, as Mark Twain commented “Buy land, they are not making it any more”. The message about land not being made any more is absolutely correct, we therefore have no option but to optimise the utilisation of the land available and make it more productive, in terms of yield per hectare and utilisation per hectare per year.

There is no doubt that Mechanisation, in its broadest sense, needs to be implemented and made available to the sub-Saharan region and increase and improve productivity and profitability of the agro-industrial complex of the region if a humanitarian catastrophe is to be avoided.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of TractorExport. This Newsletter is a free service and TractorExport cannot be held responsible for the use which may be made of the information contained therein.

If you wish to contact the author you can write an email to:

If you liked this article we invite you to share it on Facebook